Between 1945 and 1949, the U.S. State Department’s stance on Taiwan’s status was shaped by a mix of strategic, geopolitical, and practical considerations in the complex post-World War II landscape. Rather than pushing for Taiwanese independence, U.S. policymakers largely supported de facto control of the island by the Republic of China (ROC). Here’s a breakdown of why the U.S. did not advocate for Taiwan’s independence during this period:

- Wartime Declarations and Diplomatic Commitments:

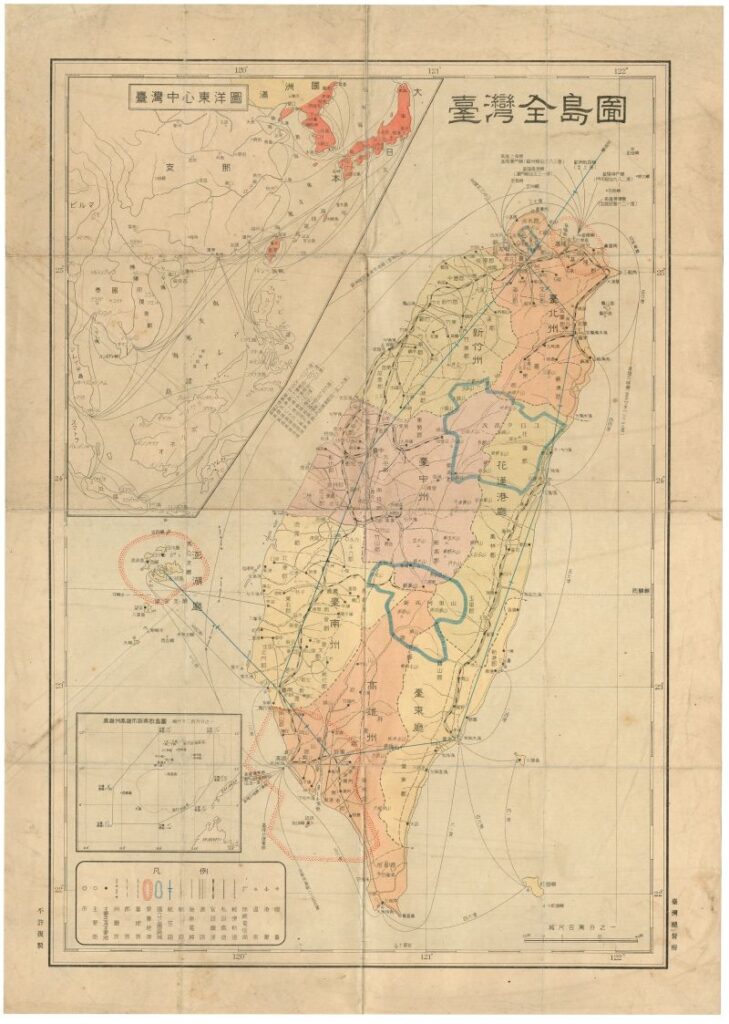

The 1943 Cairo Declaration, issued by the U.S., UK, and China, stated that Taiwan (then known as Formosa), which had been a Japanese colony since 1895, “shall be restored to the Republic of China” after Japan’s defeat. This intention was reaffirmed in the 1945 Potsdam Declaration. While these statements were political declarations rather than binding legal treaties, they set the diplomatic tone for postwar expectations. The U.S. was inclined to honor its wartime pledges to the ROC under Chiang Kai-shek, treating Taiwan’s transfer to Chinese control as the default outcome.

- Focus on Containing Communism:

The U.S. prioritized stabilizing China under the Nationalist government (ROC) to counter the growing threat of Soviet influence and the rise of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Supporting Taiwanese independence could have undermined Chiang’s legitimacy and fragmented Chinese territory at a time when U.S. policy aimed to bolster a unified, non-communist China. The State Department viewed Taiwan as an essential part of this broader anti-communist strategy.

- Taiwan’s Legal and Administrative Status:

After Japan’s surrender in 1945, Allied commanders authorized Chiang Kai-shek’s forces to accept Japan’s surrender in Taiwan, leading to ROC administration of the island. However, Taiwan’s legal status remained unresolved until the San Francisco Peace Treaty in 1951, in which Japan formally renounced sovereignty over Taiwan without designating a recipient. The U.S. acknowledged ROC administration de facto, but did not recognize de jure sovereignty, maintaining a stance of strategic ambiguity. At the time, the State Department saw no need to challenge this arrangement, which aligned with wartime understandings and required no major policy shift.

- Weakness of Local Independence Movements:

During this period, there was no robust, internationally recognized movement advocating for Taiwanese independence. While some Taiwanese intellectuals and former elites resented both Japanese colonial rule and ROC governance, the political landscape was fractured and lacked organized leadership or mass mobilization. Even after the brutal suppression of dissent in the 1947 February 28 Incident, the idea of independence had not yet gained significant traction. As a result, the U.S. had little incentive to back a nebulous cause that could alienate the ROC and complicate regional stability.

- Preoccupation with the Chinese Civil War:

The intensifying civil war between the Nationalists and Communists dominated U.S. attention in East Asia. The State Department focused on supporting Chiang’s regime with military and economic aid, hoping to stave off a Communist takeover of China. Any push for Taiwanese independence would have been a distraction from this primary objective and risked alienating an already embattled ROC government.

- Geopolitical Pragmatism in the Early Cold War:

With the onset of the Cold War, the U.S. had little interest in creating a potentially unstable new state in Taiwan that might fall prey to communist influence or become a source of regional instability. ROC control over Taiwan ensured a friendly government in a strategically significant Pacific location, aligning with U.S. efforts to maintain influence in Asia and check Soviet expansion.

- Bureaucratic Ambiguity and Policy Drift:

Internal debates within the U.S. government also played a role. The State Department was divided over how strongly to support Chiang’s increasingly authoritarian and corrupt regime. Taiwan’s long-term status was considered a secondary issue, and with no clear policy consensus, the U.S. defaulted to the status quo—recognizing ROC administration without pushing for a formal resolution or an independent Taiwan.

In summary, the U.S. State Department did not promote Taiwanese independence between 1945 and 1949 because it prioritized diplomatic commitments, Cold War strategy, and regional stability over endorsing a new and uncertain national project. Although Taiwan’s legal status remained unresolved, the de facto transfer of administrative control to the ROC was treated as a practical solution. In the eyes of U.S. officials, this arrangement upheld wartime promises, supported anti-communist goals, and avoided unnecessary complications during an already volatile period in East Asia.

______________________