Whether Chiang Kai-shek bears personal responsibility for “losing” China to the Communists during the Chinese Civil War is a debated topic among historians. Arguments on both sides hinge on his leadership, military strategy, political decisions, and the broader geopolitical context. Here’s a breakdown of the debate:

Arguments Supporting Chiang’s Personal Responsibility

1. Strategic Missteps:

Chiang’s military decisions frequently undermined the Nationalist (Kuomintang, or KMT) cause. In the 1930s, he prioritized eradicating the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) over resisting Japanese aggression – despite Japan’s occupation of Manchuria beginning in 1931. This alienated many Chinese who wanted a united resistance against foreign invasion. It wasn’t until the 1936 Xi’an Incident, in which he was detained by his own generals and forced into a United Front with the CCP, that Chiang shifted priorities.

During the resumed Civil War after 1945, Chiang overextended KMT forces into Manchuria, a region recently vacated by Soviet troops who had armed the CCP with captured Japanese equipment. Ignoring advisers who urged consolidation in the south, Chiang’s move culminated in the 1948 Liaoshen Campaign, a catastrophic defeat that handed the Communists control of key industrial areas.

2. Political Failures:

Chiang’s authoritarianism and insistence on centralized control alienated potential allies. He marginalized capable regional leaders and warlords, valuing loyalty over effectiveness. This approach fractured the KMT internally. Moreover, his government was plagued by corruption and economic mismanagement, leading to hyperinflation by 1948. The regime’s failure to deliver economic stability or reform alienated the population.

In contrast, the Communists gained grassroots support, especially among peasants, through effective land reform and promises of social equity. Chiang failed to offer a compelling alternative to win the “hearts and minds” of ordinary Chinese.

3. Underestimating the Communists:

Chiang’s 1927 purge of Communists from the KMT (the Shanghai Massacre) launched a decades-long civil conflict. Despite setbacks like the Long March (1934–1935), the CCP regrouped in Yan’an and steadily built strength. Chiang, however, continued to see them as a secondary threat or a spent force. After World War II, he relied on superior troop numbers and U.S. aid, underestimating the CCP’s morale, guerrilla tactics, and organizational sophistication.

4. Loss of Popular Support:

Chiang’s policies favored elites and landlords, neglecting the rural majority. His New Life Movement – a campaign promoting Confucian values and moral reform – was seen by many as out of touch with wartime realities. Meanwhile, Mao Zedong’s promises of land redistribution and egalitarianism resonated with the impoverished peasantry. Chiang’s inability to adapt or reform lost him crucial popular support during a people-driven war.

Arguments Against Chiang’s Sole Responsibility

1. External Pressures:

Chiang faced immense challenges beyond his control. The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) devastated China’s infrastructure and military resources, especially in KMT-held regions. By contrast, the CCP preserved its strength in rural areas and expanded influence while the KMT bore the brunt of the fighting. After the war, the Soviet Union transferred Japanese arms to the CCP in Manchuria, giving Mao’s forces a significant advantage.

2. U.S. Policy Failures:

Although the U.S. was Chiang’s main foreign supporter, its aid was inconsistent and often counterproductive. General George Marshall’s mediation efforts in 1945–46, which aimed to form a coalition government, included an arms embargo on the KMT at a critical time. Later U.S. aid was poorly managed, arriving too late or being siphoned off by corrupt officials. Some American policymakers also underestimated the Communist threat and were divided over the extent to which they should support Chiang’s struggling regime.

3. Communist Strengths:

The CCP was not merely the beneficiary of KMT blunders; it excelled in many areas. Mao’s leadership adapted to changing conditions, and the Long March forged a loyal, disciplined core. The CCP’s emphasis on political education, local engagement, and land redistribution helped it outmaneuver the KMT in both strategy and propaganda. Their success was not simply due to Chiang’s failures but also to their own strengths and innovations.

4. Structural Challenges and Historical Conditions:

Some scholars argue that China’s collapse into Communist rule was shaped by long-standing structural issues: centuries of peasant exploitation, warlordism, and foreign intervention had left the country fragmented. The KMT’s 1928 unification of China was tenuous at best. The devastation of the war with Japan further destabilized the situation. In this view, no leader – regardless of competence – could have held China together in the face of such conditions and an insurgent Communist force supported by the Soviet Union.

Synthesis: A Mixed Verdict

Chiang Kai-shek’s personal responsibility for the Nationalist defeat is significant, but not absolute. His strategic misjudgments, political rigidity, and failure to address corruption and reform opened the door for Communist gains. His emphasis on authoritarian control and elite interests left him disconnected from the population he needed to mobilize.

Yet Chiang operated under extreme pressure: a country ravaged by war, unreliable allies, and a formidable ideological opponent. As historian Odd Arne Westad notes, the CCP triumphed not only because of their strengths but also because they made fewer mistakes than the KMT. The fall of mainland China was thus a combination of Chiang’s shortcomings and external forces beyond his control.

Conclusion

Chiang Kai-shek bears substantial blame for the Nationalist defeat in China, but to place sole responsibility on him oversimplifies a complex historical collapse. The Chinese Civil War’s outcome was as much Mao’s strategic success as it was Chiang’s failure – shaped by a chaotic era in which no single individual held full control.

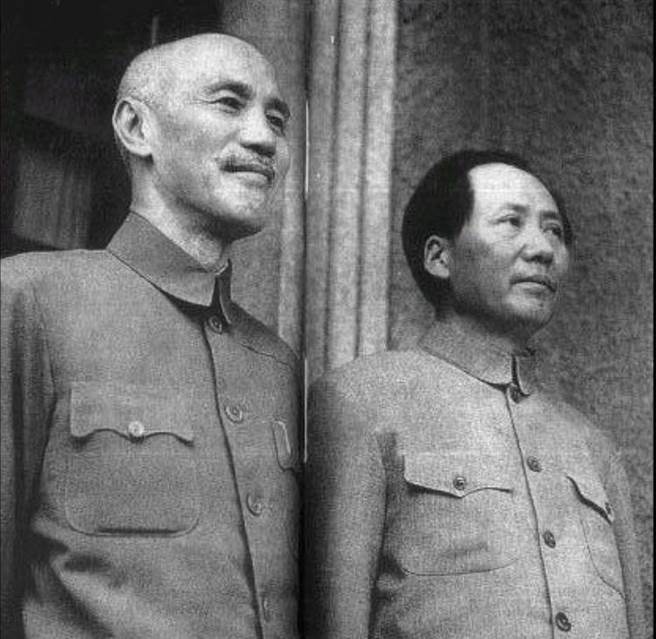

Chiang Kai-shek and Mao Zedong in Chongqing in 1945

______________________