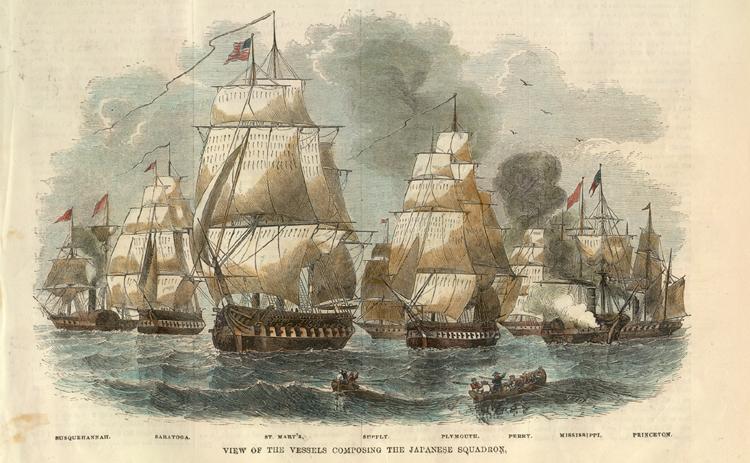

On his way back to Japan in 1854, U.S. Commodore Matthew C. Perry anchored off Keelung in Formosa, modern-day Taiwan, for ten days. In his official reports, Perry highlighted the island’s strategic value, describing it as a well-positioned midpoint for trade and a defensible outpost ideal for American expansion in East Asia. He even compared its potential role to that of Cuba for the Spanish in the Americas. Perry believed that occupying Formosa could help the United States challenge growing European dominance over key trade routes. Despite his recommendations, the U.S. government took no action to assert sovereignty over the island. This raises a question of alternative history: How might history have developed differently for the island that is known today as Taiwan had the U.S. actually decided to occupy Formosa in the 1850s? A separate question: On what legal grounds might such a move have been justified?

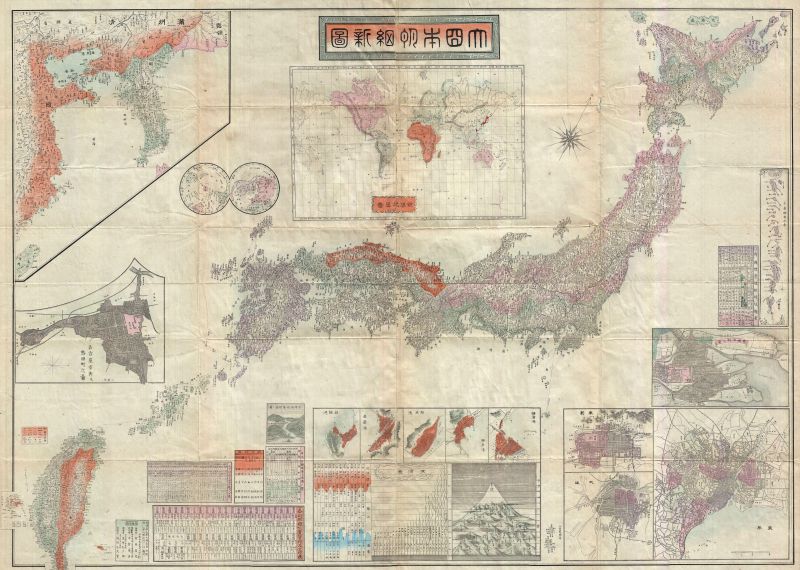

A map of the Empire of Japan including Taiwan in 1895

Alternate History: U.S. Occupation of Formosa in the 1850s

If the United States had occupied Formosa (modern-day Taiwan) in the 1850s following Commodore Matthew C. Perry’s proposal, the island’s historical trajectory, as well as regional and global dynamics, could have diverged significantly. Below is a speculative exploration of how history might have unfolded:

Strategic and Economic Implications:

- Trade Hub: Formosa’s occupation would have positioned the U.S. as a major player in East Asian trade, leveraging the island as a mid-way point between China, Japan, and Southeast Asia. American merchants could have dominated trade routes, challenging British, French, and Dutch influence.

- Military Stronghold: As Perry noted, Formosa’s defensible geography could have made it a key naval base, akin to Cuba for Spain. This would have given the U.S. a strategic foothold to project power in the Pacific, potentially deterring European colonial ambitions and influencing conflicts like the Opium Wars.

- Economic Development: American investment might have spurred early infrastructure development, such as ports, railways, and telegraph lines, transforming Formosa into a commercial hub earlier than its historical industrialization under Japanese rule (1895–1945).

Impact on Regional Powers:

- Qing China: The Qing Dynasty, which nominally controlled Formosa, was weakening in the 1850s due to internal rebellions (e.g., Taiping Rebellion) and external pressures. A U.S. occupation might have provoked diplomatic protests but likely no military response, given Qing limitations. However, it could have accelerated China’s perception of foreign encirclement, possibly intensifying anti-Western sentiment.

- Japan: Japan, opened to trade by Perry’s missions, might have viewed U.S. control of Formosa warily, especially as it modernized post-Meiji Restoration (1868). This could have led to earlier tensions or alliances, altering Japan’s imperial ambitions toward Taiwan in 1895.

- European Powers: Britain and France, dominant in Asia, would likely have opposed U.S. expansion, fearing competition. This might have led to diplomatic friction or even proxy conflicts, though outright war would have been unlikely given shared Western interests.

Formosa’s Sociopolitical Evolution:

- American Governance: The U.S. might have administered Formosa as a territory, similar to Hawaii or the Philippines later. This could have introduced American legal systems, education, and Protestant missionary activity, reshaping local culture alongside indigenous and Chinese influences.

- Indigenous and Settler Dynamics: The U.S. would have faced challenges managing Formosa’s indigenous populations and Chinese settlers. Policies might have mirrored those toward Native Americans, potentially leading to displacement or assimilation efforts, with long-term demographic and cultural impacts.

- Path to Statehood or Independence: Depending on U.S. policy, Formosa could have followed a trajectory like Hawaii (annexation and statehood) or the Philippines (eventual independence). By the 20th century, Formosa might have emerged as a U.S. state, a self-governing territory, or an independent nation with strong American ties.

Global Ramifications:

- U.S. Imperial Trajectory: Occupying Formosa would have accelerated America’s imperial ambitions, potentially leading to earlier involvement in Pacific conflicts or colonization efforts elsewhere in Asia.

- World Wars and Cold War: A U.S.-controlled Formosa might have altered Pacific dynamics during World War II, possibly preventing Japanese occupation. In the Cold War, it could have been a staunch U.S. ally, shifting regional balances against China and the Soviet Union.

- Modern Taiwan: Today, Formosa might resemble a Pacific version of Hawaii or Guam, with a unique blend of American, Chinese, and indigenous identities. Its geopolitical role could mirror Singapore’s as a trade and military hub, with less ambiguity over sovereignty than modern Taiwan faces.

Legal Justification for U.S. Occupation

The U.S. could have attempted to justify occupying Formosa legally in the 1850s using frameworks common to 19th-century imperialism, though the justification would have been contentious. Possible approaches include:

Terra Nullius or “No Sovereign Control”:

- The U.S. could have argued that Formosa was effectively under no strong sovereign control, given the Qing Dynasty’s loose governance over the island (limited to coastal areas, with indigenous groups dominating the interior). This claim, akin to justifications for colonizing Australia, would have ignored Qing nominal authority and indigenous rights but aligned with Western colonial logic.

Strategic Necessity and Trade Rights:

- Citing the need to secure trade routes and counter European monopolies, the U.S. could have framed occupation as a defensive measure to protect American commercial interests. Perry’s reports emphasized Formosa’s strategic value, which could have been presented as justifying preemptive control to ensure “freedom of commerce.”

Treaty or Purchase:

- The U.S. might have sought a treaty with the Qing Dynasty, exploiting China’s weakness to cede or lease Formosa, similar to Britain’s acquisition of Hong Kong in 1842. Alternatively, a nominal purchase (like the Louisiana Purchase) could have been proposed, though Qing resistance to ceding territory outright would have been likely.

Civilizing Mission:

- Echoing the “white man’s burden,” the U.S. could have claimed a duty to “civilize” Formosa’s indigenous peoples and Chinese settlers, introducing Christianity, education, and governance. This paternalistic rationale was common in U.S. expansion (e.g., Native American policies) and European colonialism.

Precedent of Exploration:

- Drawing on Perry’s analogy to Cuba’s role for Spain, the U.S. could have argued that occupying Formosa was a natural extension of its exploratory and commercial rights, akin to earlier claims over uncharted territories in the Americas.

Challenges to Legality:

- Qing Sovereignty: The Qing Dynasty, though weak, maintained recognized sovereignty over Formosa, and occupation without treaty or conquest would have violated international norms, risking condemnation from China and European powers.

- Domestic Opposition: U.S. anti-imperialists and those wary of overexpansion (especially amid sectional tensions over slavery) might have challenged the legal and moral basis for occupation.

- International Backlash: European powers, particularly Britain, might have contested U.S. claims diplomatically, citing their own treaties with China or invoking balance-of-power concerns.

Conclusion

A U.S. occupation of Formosa in the 1850s could have transformed the island into a key American outpost, reshaping East Asian trade, regional power dynamics, and Formosa’s cultural identity. It might have accelerated U.S. imperialism while complicating relations with China, Japan, and Europe. Legally, the U.S. would likely have relied on dubious colonial-era justifications, exploiting Qing weakness and framing occupation as a strategic and civilizing necessity, though such claims would have faced significant diplomatic and ethical scrutiny.

Commodore Perry’s fleet for his second visit to Japan, 1854